Trust is everywhere in business—but rarely treated like it matters.

It shows up in values statements, leadership models, and culture decks. But for something so frequently discussed, it’s surprisingly misunderstood.

Most organizations treat trust as something you can declare or communicate. In reality, it’s built—or broken—through how people experience leadership, decisions, and systems over time. And in today’s volatile environment—full of change, complexity, and rising expectations—those experiences matter more than ever. Trust isn’t just about making people feel good. It’s what allows people to move forward when clarity is scarce. It’s what holds culture together when the ground is shifting. And it’s what enables the behaviors that keep organizations both agile and human-centered.

Understanding how trust works—and how to design for it—isn’t just a leadership advantage. It’s a strategic necessity.

The Power of Trust

Trust shapes behavior. In high-trust environments, people don’t just feel safer—they show up differently. They speak up. They lean in. They move forward with more resilience and less friction.

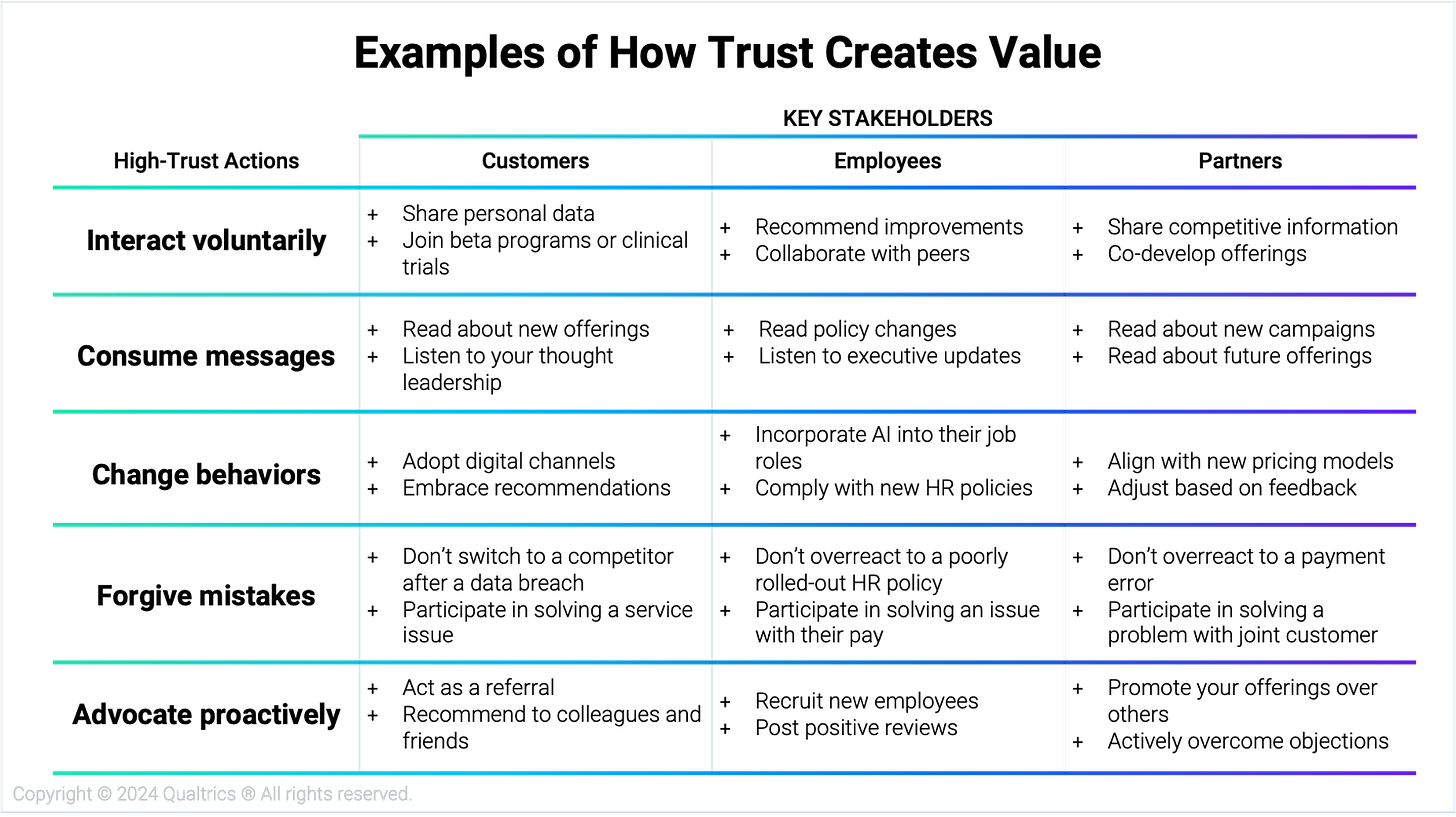

Here are five foundational behaviors that trust unlocks:

- They interact voluntarily. In low-trust settings, people wait for direction or stay silent to protect themselves. But when trust is strong, people participate without prompting. They offer ideas, raise concerns, and step into challenges—because they believe their input will be respected.

- They consume information more openly. Without trust, people second-guess even well-intentioned messages. They assume spin or hidden agendas. But in high-trust environments, communication is absorbed more easily. People take information at face value and spend less energy trying to interpret what’s not being said.

- They change behaviors more easily. In environments of low trust, change feels risky. People wonder: Will I be blamed? Can I rely on support? But when trust is present, those fears fade. People are more willing to try new things, take feedback, and shift how they work—because they trust the intent behind the ask.

- They forgive mistakes. Without trust, mistakes are treated as signs of incompetence or carelessness. With trust, people believe errors are honest and that there will be a sincere effort to make things right. That belief opens the door to recovery, learning, and continued commitment.

- They advocate proactively. In low-trust cultures, people may stay quiet—even when they care. But when trust is strong, people actively promote the organization. They recommend it to others, defend it when it’s challenged, and identify with its purpose.

How Trust Really Works

“The willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party.”

In this definition, the “trustor” is the person or entity deciding whether to place their trust, and the “trustee” is the individual or organization being trusted.

This definition highlights three essential components that shape trust:

- Ability: The skills, competencies, and characteristics that enable the trustee to perform effectively in a specific area. Without evidence of competence, the trustor hesitates to trust.

- Benevolence: The genuine intent of the trustee to act in the trustor’s best interest. This emotional aspect involves believing the trustee genuinely cares and will act with fairness and empathy.

- Integrity: Consistent adherence by the trustee to a set of principles and values that the trustor finds acceptable. Integrity provides reassurance that actions will align predictably with stated commitments.

And that belief depends on two critical factors:

- The mindset of the trustor: This includes their personality, risk tolerance, and past experiences. Each trustor approaches trust decisions differently, influenced significantly by their individual history and psychological traits.

- The perceived qualities of the trustee: These qualities are directly related to the trustor’s assessment of the trustee’s competence, fairness, empathy, and consistency. These perceptions shape whether the trustor feels safe in taking the risk of trusting.

In simpler terms, trust is what encourages (or discourages) the trustor to take a risk with another person or organization (the trustee). It’s what makes people speak up, take initiative, or share uncertainty—even when they can’t fully predict how the trustee will respond.

The Two Dimensions of Trust

Trust is multidimensional, comprising cognitive and affective dimensions that collectively influence all human relationships—whether personal, professional, or between organizations and customers.

- Cognitive Trust: This form of trust is based on rational assessment and evidence. It builds incrementally through consistent demonstrations of reliability, competence, and predictability. Cognitive trust strengthens when individuals consistently see promises being kept, products delivered as expected, and information communicated transparently and accurately.

- Affective Trust: Affective trust arises from emotional bonds and meaningful connections. It develops when individuals feel genuinely cared for, understood, and valued through empathetic and supportive interactions. Affective trust grows when people experience responsiveness and compassion, especially during times of difficulty or uncertainty.

Trust, in the Real World

Together, cognitive and affective trust create a robust foundation that affects the depth and resilience of relationships across various contexts. Here’s how it might look in a real life enviornment….

Picture a hospital, where trust is constantly being tested and earned—by both patients and employees. A patient preparing for surgery builds cognitive trust as they learn about the surgeon’s credentials, read success stories, and see that the hospital follows rigorous safety protocols. That trust deepens into affective trust when the surgeon takes time to explain the procedure clearly, makes eye contact, and checks in with genuine concern for how the patient is feeling—not just physically, but emotionally.

Meanwhile, a nurse on that same surgical team builds cognitive trust in leadership when schedules are clear, safety equipment is always stocked, and decisions are communicated transparently. Affective trust develops when their manager asks how they’re holding up during a busy stretch, or steps in to support without being asked. In both cases, trust isn’t just a concept—it’s a lived experience that determines how confidently people show up and how connected they feel to the mission, the system, and each other.

How Trust Falls Apart

Trust is slow to build—and quick to break. It’s more fragile than many leaders realize.

Sometimes it wears down gradually, through subtle patterns of misalignment or neglect. Other times, a single misstep—a rushed decision, a vague explanation, an ignored concern—can trigger a shift in how people show up. But it’s not just the moment itself that breaks trust. It’s the silence, inconsistency, or lack of follow-through that comes after.

At its core, trust is built on two beliefs: Can I rely on you? and Do you care about me? When either one falters—when logic or empathy slip—trust starts to erode. And restoring it isn’t a matter of saying the right things. It takes visible accountability, consistent action, and a genuine effort to rebuild what’s been lost.

Here are some of the most common ways trust gets quietly undermined:

- Making decisions without context or explanation. People don’t expect to weigh in on every choice, but they do need to understand how decisions are made. When leadership skips over the “why”—especially on things that impact people’s work or wellbeing—it creates a vacuum. That vacuum gets filled with assumptions, doubt, and disengagement.

- Saying the right things—but rewarding the wrong ones. A company might highlight values like empathy, innovation, or collaboration—but if promotions and recognition consistently go to those who operate through control, speed, or self-interest, people notice. When there’s a gap between what’s said and what’s incentivized, trust gives way to cynicism.

- Asking for input—then going silent. Leaders often say they value feedback. But when people take the risk to speak up and hear nothing in return, the silence speaks louder than the question ever did. It signals that voices don’t matter—or worse, that asking was just for show.

- Inconsistent care and responsiveness. People watch how leaders show up—especially in moments of challenge or discomfort. When empathy is applied unevenly—some teams get grace while others face scrutiny—it creates a sense of favoritism or neglect.

- Breaking patterns people have come to rely on. Trust is built on expectations being met. When those expectations suddenly shift—with no warning or clear reason—people are left feeling destabilized. That’s especially true for small routines that communicate consistency: weekly check-ins that vanish, open-door policies that quietly close, or decision-making principles that get overridden when things get tough.

Strategies for Building Trust

Trust doesn’t just emerge—it’s built through how the system operates. That includes how information is shared, how decisions are made, and how people experience the day-to-day rhythms of work. Here are five organizational strategies for building trust at scale:

- Lower perceived risk. People are more willing to trust when the perceived downside feels manageable. Organizations can reduce perceived risk by clearly communicating safeguards, contingency plans, or evidence that outcomes are unlikely to be harmful. For example, when rolling out a new system, leaders might say, “This won’t affect your existing data, and you can revert changes at any time”—reducing fear of loss or disruption.

- Reduce uncertainty about outcomes. When outcomes feel wildly variable, trust erodes. Narrowing the range of possibilities can help people feel safer. This might mean sharing data from similar situations (“In 90% of cases, this process takes less than two weeks”) or showing that others like them have had consistent results. The goal isn’t false precision—it’s making the future feel more navigable.

- Define clear next steps. Trust often falters when people don’t know what happens next—or when. By providing clear signposts, timelines, and what’s required at each stage, organizations make long or ambiguous journeys feel more manageable. Whether it’s onboarding, performance reviews, or policy changes, mapping the path reduces anxiety and builds forward momentum.

- Set expectations upfront. People don’t just want to know what’s happening—they want to know what to expect. Sharing the reasoning behind a decision, the principles guiding it, and what success will look like builds cognitive trust by reinforcing clarity and intent. It also helps avoid surprises that might feel like bait-and-switch tactics.

- Normalize dialogue around risk and ambiguity. Organizations that openly name uncertainty tend to be trusted more—not less. Leaders can build affective trust by acknowledging what’s unknown and demonstrating care in how ambiguity is managed. Saying, “We’re navigating new terrain, but here’s what we’re watching and how we’ll communicate updates” reassures people that someone is steering the ship with awareness and empathy.

Sparking New Leadership Thinking

- Ask what really matters to people. Leaders often default to tracking progress, but trust deepens when they show real interest in how people are doing—not just what they’re doing. Questions like, “What’s been weighing on you lately?” or “What’s one thing you wish you could say more freely?” invite honest conversation. This lowers the emotional risk of being vulnerable (affective trust) and shows that people’s perspectives—not just their output—are valued.

- Pause before jumping in with answers. In moments of confusion or tension, it’s tempting to rush into solutions. But saying things like, “Let’s sit with this for a moment,” or “You don’t need to have the answer now,” creates emotional space. This signals care and patience (affective trust) and helps people think more clearly before reacting (cognitive trust).

- Let others speak first. Saying, “I’d really like to hear your thoughts before I weigh in,” shifts the power dynamic and invites contribution. It shows that input shapes direction, which reinforces openness and fairness (cognitive trust), while also making people feel respected and heard (affective trust).

- Ask people to reflect instead of correcting them. When something goes off track, asking, “What do you think happened?” or “What would you do differently?” invites learning instead of blame. This reinforces competence and autonomy (cognitive trust) and builds connection by signaling belief in the other person’s judgment (affective trust).

- Follow through on what you say. When leaders keep their word—whether it’s following up on feedback, sticking to a decision, or showing up as promised—they prove they can be counted on. This reliability strengthens cognitive trust by reducing uncertainty. Over time, consistency builds a dependable foundation where people don’t have to second-guess what leaders will do.

The Bottom Line

Trust is the foundation that drives commitment, engagement, and advocacy, especially in times of change. It’s built or broken by how people answer two questions: Can I rely on you? and Do you care about me?